Domination and Resistance: The United States and the Marshall Islands during the Cold War

Domination and Resistance: The United States and the Marshall Islands during the Cold War

Contents

-

-

-

-

-

-

Nuclear Nomads Nuclear Nomads

-

The Return to Bikini as Research Subjects The Return to Bikini as Research Subjects

-

Protest and Resistance Protest and Resistance

-

Environmental and Health Hazards on Bikini Atoll Environmental and Health Hazards on Bikini Atoll

-

The Ongoing Struggle for Justice The Ongoing Struggle for Justice

-

-

-

-

-

Epilogue: Legacies of US Cold War Policies and the Ongoing Quest for Justice in the Marshall Islands

-

-

Two US Nuclear Experiments and the Bikinians: The “Nuclear Nomads” Revisited

-

Published:January 2016

Cite

Abstract

Chapter Two explains why the United States decided to test 23 nuclear weapons at Bikini Atoll between 1946 and 1958. It also discusses the effects and implications of the US testing program on Bikini. More specifically, it examines the consequences of the US decision to remove the Bikinians to other atolls (Kwajalein, Rongerik, and Kili) and the health and environmental conditions experienced by the community as a result of their prolonged displacement. As well, this chapter discusses the Bikinians’ role as research subjects during their ill-fated return to Bikini in 1969, and their second exodus from the contaminated atoll in 1978. In addition, it emphasizes the Bikinians’ protest against the United States — in the form of petitions, council meetings, letters, telegrams, and lawsuits — and their ongoing attempts to gain adequate compensation from Washington.

Between 1946 and 1958, Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union grew over issues such as Berlin, Korea, the Middle East, and the nuclear arms race. During this period, the United States conducted twenty-three nuclear explosions at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. These experiments contributed to the development of a powerful nuclear arsenal and strengthened the American strategy of deterrence, but they had devastating consequences for the people of Bikini and their environment. Like the Enewetakese, the Bikinians were displaced from their homeland and the ecology of their atoll was seriously damaged by the nuclear tests. To draw attention to their plight and gain compensation from the American government, the Bikinians fought back using methods similar to those employed by the people of Enewetak, including petitions, hearings, and lawsuits. In response to this pressure, the United States provided the islanders with various financial packages and encouraged them to return to their contaminated atoll. Although the return of the Bikinians provided American scientists with an opportunity to study the effects of prolonged human exposure to radiation, it resulted in serious health conditions. The islanders were left on Bikini for almost ten years before they had to be removed a second time due to the unsafe levels of radiation on the atoll. Afterward, the Bikinians continued to fight for justice, but Washington failed to supply enough funds to restore the ecology of their atoll or to adequately compensate them for the damages caused by the nuclear testing program.

In 1946, President Harry Truman’s decision to go ahead with Operation Crossroads, the first series of nuclear tests on Bikini Atoll, was reinforced by top military leaders, including Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal and Army Chief of StaffGeneral Dwight D. Eisenhower. On nationwide radio broadcasts, these influential officials argued that the tests on Bikini were necessary for “national defense” and to “save American lives.”1Close As the United States began to develop a hardline containment policy against the Soviet Union, these leaders helped convince the American public that nuclear weapons tests were vital to national security.2Close

US military officials selected Bikini Atoll as a nuclear testing site for a variety of reasons. Like Enewetak, Bikini was already in the control of the United States and it was situated in a remote location in the Central Pacific Ocean, far from the continental United States.3Close Comprising twenty-six islands, Bikini was about 250 miles from the airstrip on Kwajalein Atoll, and had enough land mass to support the necessary testing equipment and facilities. It also had a large, sheltered, lagoon of approximately 245 square miles for the anchorage of American ships. As well, Bikini had a small indigenous population that could be easily transported to another atoll. As Vice Admiral William Blandy explained, “It was important that the local population be small and co-operative so that they could be moved to a new location with a minimum of trouble.”4Close

On 10 February 1946, Navy Commodore Ben Wyatt, the American military governor of the Marshall Islands, informed the Bikinians that their atoll had been chosen as the site where the United States would test new and powerful weapons. Knowing that many of the Bikinians had been converted to Christianity, Wyatt told the people that they were “like the children of Israel whom the Lord saved from their enemy and led into the Promised Land.”5Close He then asked the iroij of the atoll, Tomaki Juda, if he and his people would be willing to give up their atoll for the “benefit of all mankind and to end all world wars.”6Close

Soon after Wyatt made this presentation, the Bikinians agreed to the Americans’ request. According to Alab Lore Kessibuki, the people consented to leave their atoll because they were afraid of the United States and “didn’t feel we had any other choice but to obey the Americans.”7Close During World War II, the Bikinians witnessed the power of the United States firsthand and were impressed by its decisive defeat of the Japanese, which included the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Furthermore, the Bikinians were led to believe that their move from Bikini would be temporary. Although the islanders were not provided with a specific deadline, the Americans gave the Bikinians the impression that they could return to their homeland once the United States no longer needed it as a nuclear testing site.8Close

Nuclear Nomads

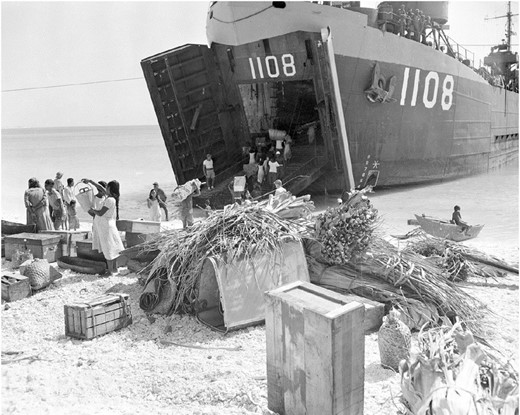

According to the US Navy’s public statements, the “natives” of Bikini were “delighted” to be moving from their ancestral lands and “enthusiastic about the atom bomb, which has already brought them prosperity and a new promising future.”9Close American officials offered the Bikinians the choice of moving to one of three other atolls in the Marshalls. Since two of these were already occupied, the Bikinians chose Rongerik, an uninhabited atoll, located 140 miles east of Bikini.10Close Surrounded by the media, 167 Bikinians and their possessions were loaded on an

Families transferring their homes from Bikini to Rongerik, 1946.

LST on 7 March 1946, less than a month after being told that they were to be moved. The navy assured them that Rongerik was actually a better place to live than Bikini: “Rongerik is about three times larger than Bikini…. Coconuts here are three or four times as large as those on Bikini and food is plentiful.”11Close

Prior to their removal, the islanders had relied almost exclusively upon Bikini’s land and lagoon for their food and material needs. Bound together by ties of kinship, they had developed a well-integrated society based on a close connection to the land. Under traditional Marshallese law and custom, each Bikinian was born with land rights in the islands of their atoll. These rights were intended to provide security to the members of the community. Because land in the Marshall Islands was scarce, the inhabitants did not regard it as a commodity that could be sold. Each individual was identified with the land that was perceived as his birthright, and ties to the land were therefore very strong.12Close

Despite the importance that the people of Bikini attached to their land, the United States formally established its control of the atoll through a use and occupancy agreement in April of 1946. For a sum of $10, the government of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands granted the United States the “exclusive right to use and occupy” all of the Bikini Atoll “for an indefinite period of time.” This document was signed by two American representatives, High Commissioner Delmas Nucker, on behalf of the TTPI government, and Navy Rear Admiral J. F. Jelley, on behalf of the United States.13Close Significantly, no members of the Bikini Council were asked to sign the agreement.14Close

Once Washington established its formal control of Bikini through the use and occupancy agreement, the United States prepared the atoll for the Operation Crossroads series of nuclear tests, described as “the grandest scientific experiment ever.”15Close The United States deployed 242 ships (70 of which were placed in the target area of the lagoon), 156 aircraft, 25,000 radiation recording devices, 42,000 military, scientific, and technical personnel and observers, and more than 5,000 animals to the Bikini Atoll.16Close

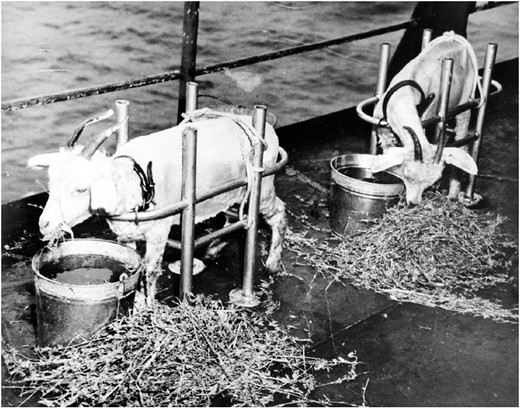

The main purpose of Operation Crossroads was to test the strength of the US Navy during an atomic attack. Due to the growing influence of the air force in planning related to nuclear weapons, the navy was keen to prove that it could play an important role in American postwar defense strategies.17Close As the navy later described it, the goal of these tests was “to study the effects of nuclear weapons on ships, equipment and material.”18Close In addition, thousands of live experimental animals were placed on the target ships to be exposed to radiation from the nuclear tests. For these experiments, American scientists utilized animals that shared similarities with humans, such as pigs and goats, so that they could gather information about the health effects of fallout on battleship crews.19Close

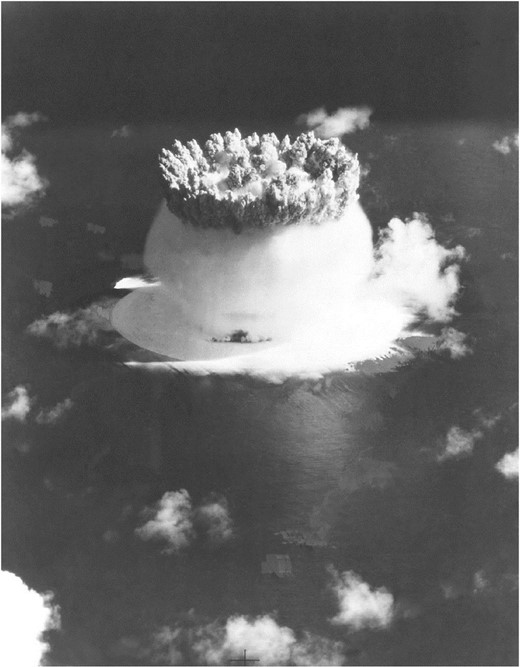

Most of the experimental animals were exposed when the first test of the series, 21-kiloton Able, was dropped from a B-29 bomber into the lagoon. Five ships were sunk by this explosion and, as Julianne Walsh explains, most of the animals “did not fare well.”20Close Of the 3,619 experimental animals on the American ships, 656 of the animals were killed by the Able blast and more than 50 percent eventually died from radiation-related illnesses.21Close Fewer animals were exposed during the second test, 21-kiloton Baker, but this underwater test had more spectacular environmental effects on Bikini Atoll. Jonathan Weisgall describes it as follows:

In one second, an underwater bomb pushed a one-mile-wide dome of water into the sky. Ten seconds later, as if in slow motion, the millions of tons of water and debris collapsed back into the lagoon, creating a gigantic curtain of mist and spray that moved outward at more than 60 miles an hour and soon engulfed almost all of the target ships. The blast, which sank the 26,000 ton battleship Arkansas in a matter of seconds, unleashed the greatest waves ever known to humanity…. It also unleashed the greatest amount of radioactivity ever known up to that time.22Close

Shorn experimental goats before Able test, Bikini, 1946.

Detonated 90 feet below the surface of the lagoon, Baker created a crater 700 yards wide and 20 feet deep.23Close The heat from the blast was so extreme that it turned the water in the lagoon to steam, resulting in a massive die-off of fish and other marine organisms. The nine ships sunk by the explosion released oil into the lagoon that destroyed the coral, algae, and shellfish on the reef of Bikini. As well, the explosion contaminated the nearby land and marine life with large amounts of radioactivity. In total, the Baker shot dumped 500,000 tons of radioactive mud on the atoll’s islands and into the lagoon.24Close

While Operation Crossroads was taking place on their home atoll, the Bikinians remained displaced on Rongerik. Contrary to the navy’s claim, the islanders discovered that Rongerik was actually much smaller than Bikini. Whereas Bikini comprised twenty-six islands (2.9 square miles of land), Rongerik consisted of seventeen islands (0.6 square miles of land).25Close The soil on Rongerik was also much less fertile than on Bikini and the lagoon considerably smaller. Within the first year of their arrival, it became apparent that food resources on Rongerik were insufficient. In July 1947 a medical officer who accompanied a field trip to Rongerik reported that the islanders were “visibly suffering from malnutrition.”26Close

Underwater Baker test, Bikini, 1946.

The United States investigated the situation but no decisions were made to improve the Bikinians’ food supply or to move them elsewhere.27Close

At the end of January 1948, Leonard Mason, an anthropologist from the University of Hawai‘i, confirmed the “extreme state of impoverishment” that characterized the Bikinians’ situation on Rongerik. In particular, Mason noted the critical water shortage and lack of food on the atoll. All of the ripe pandanus and coconut fruits had long since been consumed and there was only one bag of flour left for the 167 people living on Rongerik. At night, the anthropologist reported, it was “difficult to sleep for the frequent crying of babies who were still hungry.” As a result, Mason requested emergency food rations and medical help for the Bikinians. When an American doctor arrived on Rongerik, he briefly examined the population and declared their condition “generally to be that of a starving people.”28Close

Given their dire situation on Rongerik, Mason recommended that the Bikinians be relocated as “soon as possible.”29Close Shortly thereafter, the United States moved the islanders to Kwajalein, the largest atoll in the Marshalls, located approximately 200 miles southeast of Bikini. At the time, the Americans were in the process of transforming Kwajalein into a navy base and Marshallese workers had been recruited to work on its construction. Given Kwajalein’s designated purpose as a base, the Bikinians’ stay there was temporary; they lived on the atoll for seven months and then were moved again to the much smaller island of Kili, located approximately 280 miles southeast of Kwajalein.30Close

Only one-sixth the size of the Bikini atoll, Kili was a little over one mile in length and about one-quarter mile in width; it had a rich soil cover but no lagoon or sheltered area and poor feeding grounds for marine life. As Jack Tobin, the district anthropologist in the Marshall Islands, observed, “The change from an atoll existence [on Bikini] where marine resources were abundant and the lagoon and land areas stretched away as far as the eye could see, to a small, isolated island without a lagoon, and without the rich marine resources which are found in an atoll environment, was drastic.”31Close With no protected anchorage for vessels, Kili also experienced heavy trade winds and rough seas from November until April of each year.32Close These conditions made it impossible for the Bikinians to use their traditional outrigger sailing canoes for fishing beyond the island. As Weisgall reported, the skills the people had “developed for lagoon and ocean life at Bikini were useless on Kili.”33Close

Inadequate funding from the United States, combined with poor planning, resulted in few trust territory field trips to Kili Island.34Close This shortage of field trips affected the Bikinians in a number of ways. Although coconut trees were growing on the island, the copra that the Bikini people produced on Kili was usually spoiled or eaten by rats by the time the next field ship arrived. In addition, food shortages, which occurred in 1949, 1950, and 1952, were so common that the Bikinians became convinced that Kili was another Rongerik. They came up with an expression for their new home, “Kili enana,” meaning “Kili is no good.”35Close

Due to their problems on Kili, the Bikinians desired to return to their home atoll. According to Delmas Nucker, the high commissioner, their return was impossible because the United States had the legal right to the atoll based on the 1946 use and occupancy agreement. Under pressure from US officials, in 1951 the islanders had also signed a document entitled “Release of Rights to Bikini Atoll” granting the high commissioner “all of the right, title and interest … to the Bikini Atoll.” In exchange, the Bikinians were given use rights to Kili Island and three islets of Jaluit Atoll located about thirty miles from Kili.36Close Although thirteen Bikinian representatives were present (one iroij and twelve alabs) when the “release of rights” agreement was signed, only four signed the document and they did so without the benefit of legal counsel.37Close

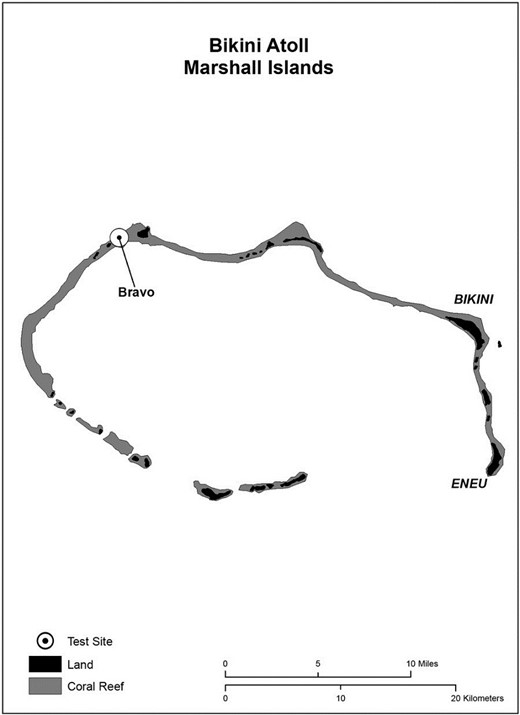

While the Bikinians were forced to remain on Kili, the United States proceeded with its nuclear testing program on their home atoll. By 1954, the United States and the Soviet Union were engaged in a race to create the most powerful thermonuclear weapons.38Close In an effort to maintain the American lead in this competition, the United States carried out Operation Castle, a series involving testing five nuclear bombs on Bikini Atoll.39Close On March 1, the largest thermonuclear test ever conducted by the United States, code-named Bravo, was detonated on the surface of the reef in the northwestern corner of the Bikini Atoll. During the first minute, this explosion released energy equivalent to fifteen million tons of TNT, produced a huge fireball, created a massive crater in the coral reef, and stripped the nearby islands of all vegetation. Within ten minutes, a radioactive cloud formed that was sixty-five miles wide.40Close

Not surprisingly, the Bikinians and other Marshall Islanders were alarmed by the Castle tests. While the series was underway, the Marshallese sent a petition to the United Nations Trusteeship Council protesting against the tests. In this petition, sent on 20 April 1954, the Marshallese brought an “urgent plea” to the UN to get the tests stopped. As they pointed out, the United Nations was the appropriate organization of appeal due to its pledge to “safeguard the life, liberty, and general well-being of the Trust Territory.”41Close

The loss of their land to the United States government was a major concern to the petitioners; in the atoll environment, land was a scarce commodity necessary for sustenance and the Marshall Islanders deemed it their most precious resource. Land had both practical and spiritual meaning in Marshallese culture. As the petition stated, “Land means more than just a place where you can plant your food crops and build your houses; or a place you can bury your dead. It is the very life of the people. Take away their land and their spirits go also.”42Close

In their petition, the Marshallese asked the United States to stop testing nuclear weapons on their islands. They also requested compensation from Washington for the Bikinians and other communities who had been forced to relocate to different atolls.43Close In its response, the State Department issued a carefully worded statement, jointly drafted by the Atomic Energy Commission and the Department

Map created by the Historical GIS Laboratory, University of Saskatchewan 2013

Note: Although the United States conducted twenty-three nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll, the author was unable to verify the site locations of the other twenty-two explosions.

of Defense. According to this statement, it was very important for the Marshall Islanders to understand that the Eisenhower administration would not be conducting nuclear tests if it had not been determined, after very careful study, that they were required in the “interests of general peace and security.”44Close

In 1956, the United States made similar statements when it announced a new series of tests, Operation Redwing. According to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), the main goal of this series was to improve American military strength for the “purposes of peace.”45Close In response, representatives for the Marshall Islanders sent another petition to the UN Trusteeship Council demanding that all nuclear experiments in the trust territory be stopped.46Close Ignoring this request, the United States went ahead with Operation Redwing between May and July 1956. In total, this series included six large nuclear explosions on Bikini Atoll, with yields ranging from 365 kilotons to 5 megatons. One observer described Tewa, the biggest blast in the series: “Tewa had … the highest known [fission yield] of any US thermonuclear test, making it the “dirtiest” bomb ever…. The Bikini barge, site of ground zero, turned into a burning ball of fire and jumped up into the air alongside the mushroom cloud. After the blast, millions of dead fish floated on the surface for miles and miles alongside tens of thousands of dead birds, scooped up by live sharks and barracuda…. Fish also inhabited the tops of coconut palms that Tewa had not blasted apart.”47Close

While the Americans proceeded with Redwing, representatives from Kili went to Majuro to convey their grievances about living on the atoll to a UN visiting mission to the trust territory. One spokesman told the mission that he and the other Bikinians did not wish to live on Kili any longer.48Close The Bikinians had suffered from starvation again in 1955 and the trust territory ships were still having trouble unloading food in the rough water around the island.49Close If they could not be returned to their homeland, the Bikinians wanted to be moved elsewhere.50Close

In November 1956, the high commissioner, Delmas Nucker, visited Kili, where he was met by Magistrate Juda and “practically the entire population of the island.” During this meeting, Nucker offered the Bikinians a new deal: If they agreed to sign another paper giving the United States “full use rights” on Bikini Atoll, Washington would grant them similar rights on Kili as well as the islets on Jaluit atoll. As there was no lagoon on Kili and the amount of land on Kili and Jaluit was much smaller than on Bikini, the Americans were also willing to provide a financial package consisting of $325,000. Nucker made it clear that this money was being offered to pay for the use of the Bikini Atoll and “everything on it” for “as long as the [US] government needs to use it for the most good for the most people of the world.” Of the total amount, $25,000 would be given to the people of Bikini in cash and $300,000 set aside in a trust fund.51Close

According to the high commissioner, this agreement, which was necessary in the interests of “international peace and security,” would be honored by Washington until it no longer needed Bikini and the atoll could be safely returned to the people. Perhaps believing that this was the best deal that they could get, and, again, without the benefit of legal counsel, several Bikini alabs signed the “Agreement in Principle Regarding the Use of Bikini Atoll” on 22 November 1956.52Close The Americans then gave the Bikinians $25,000 in one-dollar bills, to be divided equally among the people.53Close

While the Bikinians were forced to stay on Kili, the United States carried out its most extensive set of nuclear explosions in the spring and summer of 1958. This new series, “Hardtack I,” included detonations of ten nuclear weapons at Bikini, ranging in magnitude from 0.02 kilotons to 9.3 megatons.54Close Not coincidentally, this flurry of explosions took place just prior to the American decision to call a moratorium on its nuclear testing program and participate in the nuclear test ban talks, which started in Geneva in October of 1958.55Close

Although the Eisenhower administration stopped testing nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands in 1958, the people of Bikini remained displaced. In 1963 and 1964, the Bikinians sent petitions to Washington asking that they be resettled, preferably on their home atoll. They also had nagging questions about the 1956 agreement. Was it possible for them to go back to Bikini or had they given up the rights to their atoll for all time? If they were allowed to return to their homeland, would they forfeit the trust fund?56Close

As conditions continued to deteriorate on Kili, anthropologist Jack Tobin, who was also the community development adviser for the Marshall Islands, visited the island in 1968 to “ascertain the situation there.” While on Kili, Tobin observed that the shacks that the people lived in were falling apart and the water supply completely inadequate. Increasingly, the community was becoming anxious about the need to leave the island. “The anxiety level is very high on Killi [sic] now. The central thought is ‘when will we return to Bikini?’ It has become an obsession with these exiles. They have never given up the hope of returning to their home atoll. They have never become reconciled to living on Killi permanently. The situation is extremely tense and potentially explosive. I predict a dramatic and disruptive reaction if the Killi people are told that they cannot return to Bikini.”57Close

The Return to Bikini as Research Subjects

As a result of the deteriorating conditions on Kili, the Bikinians continued to pressure the Johnson administration to return them to their home atoll. Their return was problematic, however, due to the ecological condition of Bikini. A series of radiological surveys completed by the AEC indicated that Bikini Atoll remained contaminated. The results of a survey conducted in 1967 (based on gamma-ray spectrometry) showed that “a dose gradient [of radiation] existed across Bikini, with lowest levels on the beach areas, and highest values in the heavily overgrown interior.”58Close Samples of local plants and animals, which were collected at Bikini and Eneu islands during the survey, also revealed the presence of radionuclides such as cesium-137 and strontium-90.59Close

Despite these findings, Dr. Robert Conard of the Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL) and other members of an ad hoc committee assembled by the AEC recommended that the Bikinians be resettled on Bikini and Eneu islands. By this time, Conard had already carried out extensive studies on the effects of radiation on the people of Rongelap who had been repatriated to their contaminated atoll in 1957. Although these studies showed that the Rongelapese were suffering from negative health effects related to both internal and external exposure to radioactivity, the AEC concluded in 1968 that “the exposures to radiation that would result from the repatriation of the Bikini people do not offer a significant threat to their health and safety.”60Close

Radioactive coconut crab, Bikini Survey, 1964.

In July 1968, Jack Tobin participated in a radio conference with the Kili magistrate, Lore Kessibuki. The magistrate highlighted the islanders’ need for the over-due money from their trust fund and their urgent desire to return to Bikini. As Kessibuki explained, “The Kili people want to know when they can move back to Bikini. This is a question that the people think about night and day, every day, and every night.”61Close

Influenced by the AEC’s recommendations and the growing unrest on Kili, President Lyndon Johnson announced in August 1968 that Bikini and Eneu islands would be cleaned up and prepared for resettlement. According to a White House press release, Bikini Atoll was “again safe for habitation” and the United States was resolved to “work with the Bikini people in building a modern and model community on their atoll.”62Close Elated at hearing this news, the 540 Bikinians living on Kili (and other islands and atolls such as Ebeye and Majuro) looked forward to returning home. Several weeks after the president’s announcement, a delegation of islanders was taken to Bikini Atoll for a visit. But as anthropologist Robert Kiste points out, they were shocked by what they saw. “Bikini was not the idyllic homeland of their memories. A massive amount of debris and equipment left from the tests cluttered the islands and the beaches. As a result of the nuclear experiments, two or three small islands and portions of others had disappeared. Most coconut palms and other plants of economic value had been removed or destroyed, and the atoll was engulfed by a dense layer of scrub vegetation.”63Close

Given the extensive damage caused by nuclear tests, the new Nixon administration prepared an eight-year plan for the rehabilitation and resettlement of Bikini.64Close In early 1969, the Department of Defense was made responsible for the first phase of the plan, which involved the clearing of radioactive debris from Bikini Island.65Close The US trust territory government and the Department of Interior were put in charge of the second phase, which included the replanting of coconut trees, the construction of housing, and the resettlement of the Bikinians from Kili.66Close

The AEC was given responsibility for the “radiological safety” of Bikini and Eneu islands. Significantly, the agency appointed Dr. Conard to conduct “medical surveillance” of the Bikinians as they returned to their home atoll.67Close When asked about the risks involved in the resettlement of the Bikinians on their contaminated islands, Conard offered reassurance during an interview on the atoll: “Radiation levels on Bikini are so very slight and so many precautions have been taken to reduce the levels to extremely low amounts that there should not be any real hazard when these people are returned. We know from our experiences on Rongelap that the low levels of radiation there that persisted in the soil after the fallout were insufficient to cause any hazard to the Rongelap people so I wouldn’t expect that there would be any hazard here [on Bikini].”68Close

Given his extensive knowledge of the Rongelapese experience, this statement was a very odd one for Conard to make. Since 1954, Conard and other scientists working for the BNL had been conducting research studies on the Rongelapese, an atoll community located approximately one hundred miles east of Bikini, who had been exposed to large doses of radiation from the Bravo nuclear test. Based on these studies, Conard knew that the body burdens of radionuclides such as cesium-137 and strontium-90 increased dramatically after the Rongelapese (and a control group) were returned to their contaminated atoll.69Close By the 1960s, Conard’s own reports also indicated that the Rongelapese were experiencing a number of serious health conditions related to their exposure to radiation such as thyroid cancer, birth defects, and growth retardation.70Close

Despite the health hazards, the return of the Bikinians to their contaminated atoll provided Conard with another opportunity to study the movement of radioisotopes “from the environment to man.”71Close In preparation for the Bikinians’ return to their home atoll, the AEC carried out a radiological survey of the groundwater, animals, and soils of Bikini and Eneu islands. Led by Edward Held of the AEC, this survey (like an earlier one completed in 1967) showed that the well water on the two islands was contaminated with radioactive tritium, while food items such as coconut crabs, sea birds, and reef fish contained the radionuclides cesium-137, strontium-90, and plutonium-239 and-240. The soil also contained these four radionuclides, as well as iron-55, cobalt-60, and antimony 125.72Close According to Held, these radionuclides would be available to any land animals living on the islands through the ingestion of the vegetation, other animals, or the soil.73Close Given rapid advances in the technology of detection, combined with the long-lived nature of most of these fission products, Held concluded that “Bikini can be expected to remain a useful area for the study of the redistribution of radionuclides for at least several decades.”74Close

In addition to gaining data about the radiological condition of Bikini and Eneu islands, the AEC also gathered scientific information from the Bikinians in 1969. To obtain baseline data for his medical study of the Bikinians, Conard and his team collected urine samples from fourteen people living on Kili.75Close After examining these samples in New York, the BNL concluded that the Bikinians had body burdens of cesium-137 and strontium-90 that were significantly lower than those in the people living on Rongelap at the time. Since Conard expected the levels of these radioisotopes to rise once the Bikinians returned to their contaminated atoll, he planned to conduct further tests on them, including whole-body gamma spectroscopy. He predicted, however, that the increase in the Bikinians’ body burdens of cesium-137 and strontium-90 would not be “anywhere near that measured in the Rongelap people on return to their island.”76Close

In 1969, thirty-one Bikinians were moved to Eneu Island, ostensibly to begin working on the rehabilitation of Bikini Island. Although Conard decided not to provide the islanders with medical examinations, he and his Brookhaven team began annual radiological monitoring of the Bikinians using urine analysis and whole-body counting.77Close The scientists also assured the islanders that it was safe to eat the food and drink the water on Bikini and Eneu islands.78Close Based on instructions from the Americans, the Bikinians dug wells to provide water for the new trees that they were planting on the atoll. They also used the water for drinking, to cook food, to clean their clothes, and to wash themselves.79Close According to a Bikinian named Pero Joel, the workers ate the food on the islands as well:

On Eneu we had gardens and on Bikini we drank coconuts and ate pandanus all the time. I was one of the people helping to make those gardens. We were told in the beginning of our stay on Bikini that it was safe to eat anything we wanted, so we did. We had many kinds of foods, bananas and things like that. The scientists would come and explain a little about radiation, but we were always under the impression that everything was safe and that we could go about our everyday business and not worry. I used to ask them a lot of questions like, “How deep into the soil did the poison [radiation] go?” When they would answer they would say that it was about one-foot deep into the ground, but that it wasn’t anything for us to worry about.80Close

Protest and Resistance

Meanwhile, the Bikinians remaining on Kili continued to draw attention to their plight. In December 1969, Lore Kessibuki, the magistrate of Kili, sent a letter to the new high commissioner, Edward Johnston, outlining many of their grievances. Since the planting stage of the rehabilitation program had just begun on Bikini, it was obvious that the remaining people on Kili would not be able to return to their home atoll any time soon. This situation was unacceptable since the living conditions on Kili continued to worsen:

Kili is like a prison and unsuitable as a place for people to live. Our suffering on Kili is too much to endure any longer. From the months of October through February, we are unable to be serviced by ships because of surf conditions. Our copra rots on the island and we cannot buy supplies. What little fish there are cannot be caught because of the giant waves…. Our houses are falling down around us…. We are starving during the winter months. Is this the way the United States treats people who have sacrificed everything to help America with her research?81Close

Kessibuki requested that the United States pay compensation for the suffering inflicted by the removal of the Bikinians to the atoll. In addition to starvation and humiliation, the relocation caused the islanders to become increasingly dependent on the trust territory government. As well, the people of Bikini viewed the 1956 agreement as “illegal” because they were not provided with legal counsel when the document was signed. The magistrate also highlighted the damage caused by the twenty-three nuclear tests on Bikini. In particular, he emphasized the “disappearance” of some islands and the dangerous levels of radiation on others. As he pointed out, “Coconut crabs, once a part of our diet, are radioactive.” To compensate the Bikinians for the use of their atoll, their relocation, and all of the damages caused by the nuclear testing program, Kessibuki demanded that Washington pay them $100 million.82Close

When the office of the high commissioner failed to respond to the magistrate’s letter, the Kili Council sent an urgent telegram to Jack Tobin in late February 1970. In this dispatch, the islanders demanded that “WE BE MOVED TO BIKINI IMMEDIATELY. WE DO NOT WISH TO REMAIN ON KILI ANY LONGER.” In a telephone conference on 2 March 1970, Kessibuki explained that approximately 550 islanders desired to return to the home atoll en masse (approximately 370 were living on Kili and 180 elsewhere, mostly on Ebeye and Majuro). The magistrate also repeated their demand for $100 million for the “damage to their land on Bikini, and the personal hardships caused by their removal from Bikini by the [US] Government.”83Close

In a memo to the high commissioner, Tobin warned that the islanders were becoming increasingly restive and frustrated, a situation exacerbated by the poor living conditions and lack of food on Kili. If the United States refused to return them to Bikini, Tobin predicted that the islanders would continue to bombard Johnston with verbal requests and possibly send another petition to the United Nations. More seriously, he expected that they would carry out a more overt and dramatic form of protest, such as a “boat in” to Bikini or a major demonstration at Majuro.84Close

In his correspondence with the Department of the Interior, High Commissioner Johnston conveyed little sympathy for the Bikinians’ situation. While Johnston conceded that it was “apparently true,” as Kessibuki had contended, “that the people were not represented by counsel” when the 1956 agreement was signed, the people of Bikini had had “more than sufficient time to obtain counsel” since that date. Based on the 1956 agreement and the earlier 1951 “release of rights” document, he argued, the Americans possessed full use rights of Bikini Atoll. Indeed, according to the high commissioner, the United States “had complete rights to destroy portions of it [Bikini Atoll] in the testing of nuclear weapons.” Furthermore, since a “substantial sum” had already been paid to the islanders in 1956, Washington felt no legal obligation to make any additional payment for the damages to Bikini Atoll or their displacement to Kili.85Close

Without consulting the Bikinians, the United States then signed an agreement returning most of Bikini Atoll to the TTPI government. On 4 May 1970, the high commissioner sent a letter to the Kili Council informing them that the US government had signed the document two weeks earlier. This agreement, with some minor exceptions, terminated the use and occupancy that had been granted to the Americans by the TTPI government in 1946.86Close When they received this news, the Kili Council responded angrily. According to their leaders, the high commissioner had given his word that Bikini would be legally returned to them as soon as the trust territory regained control of it. As the council explained in a letter to Johnston, “We are disappointed we are not consulted before matters of importance are decided and that the High Commissioner promised to return Bikini to us as soon as he had authority to do so but this has not yet been done.”87Close

As a result of the continuing discontent expressed by the Bikinians, the attorney general of the trust territory, Robert Hefner, met with Magistrate Kessibuki and various members of the Kili Council on 4 March 1971. During this meeting, which took place at Majuro Atoll, the Bikinians described the hardships of living on Kili and their need for additional financial resources. More specifically, they requested an amendment to the 1956 trust fund agreement that would give them greater earning power and more flexibility.88Close The Bikinians also asked for additional money to compensate them for the damage to Bikini and their relocation to Kili.89Close

Based on the Bikinians’ demands, Hefner suggested that the United States make some minor adjustments to the 1956 agreement. The attorney general also advised the US Congress to pay the islanders an additional $1 million in trust money to “alleviate the living conditions on Kili.” If the government did not provide this financial assistance, Hefner warned, the Kili Council undoubtedly would send more petitions to the United States and the United Nations, which would “embarrass us before the world community.”90Close

Responding to Hefner’s advice, High Commissioner Johnston signed an amendment to the 1956 trust agreement that gave the Bikinians more flexibility regarding their investments.91Close However, Johnston was not as forthcoming regarding the Bikinians’ request for further financial compensation. As a result, the Kili Council decided to hire legal counsel to put more pressure on Washington. In a statement of grievances presented to the Nixon administration in 1973, their lawyers pointed out that the income derived from the trust fund granted in 1956 was insufficient, amounting to “no more than a pittance” when divided among the Bikini people twice a year, totaling only about $12.00 for each person. More broadly, the islanders wanted to remind the United States that:

The people of Bikini … have endured endless broken promises; three forced relocations of their homes; malnutrition and near-starvation; atomic destruction of their homeland and irradiation of their soil; deterioration of their social structure and loss of a sense of community; loss of many skills required for fishing on an atoll; isolation and rejection by the [trust territory] government; and the certain risk of living with the dangers of radioactivity. For all of this they have received a trust fund that loses money, some surplus USDA food and an isolated and miserable island far from their home. Surely the United States will not ignore their rights and complaints.92Close

The following year, the Kili Council demanded that the US Congress provide an ex gratia payment of $3 million. From the Bikinians’ perspective, this request was reasonable because the people of Enewetak had received similar compensation from the United States in 1969. The Bikinians justified this amount of money based on their twenty-seven years of suffering and hardship on Kili.93Close In Tobin’s view, the islanders had “valid reasons” for claiming compensation from the US government, as he explained in a letter to the high commissioner:

In my view, as one who has been very close to the problems of the displaced Bikini People, … they have definitely and obviously not been adequately compensated for the loss of their homeland for so many years and the damage that has been done to it…. They were not dealt with equitably…. The returns to the United States from the use of Bikini … in terms of strategic military position, political power, and the acquisition of scientific and military knowledge have been incalculable. The returns to the exiled Bikini … People have been meagre.94Close

Working on behalf of the Bikinians, lawyers from the Micronesian Legal Services Corporation (MLSC) sent letters to the Department of the Interior and to the high commissioner to request compensation.95Close Three members of the council also went to Washington to petition officials in the departments of Defense and Interior.96Close Eventually, the pressure brought by the Bikinians and others paid off. Agreeing that the islanders’ petition97Close was justified, the US Congress passed Public Law 94-34, the Hawaiian Trust Fund for the People of Bikini. Under this law, Washington provided a $3 million ex gratia payment “in recognition of the hardship suffered by the people of Bikini due to displacement from their atoll since 1946.”98Close

Environmental and Health Hazards on Bikini Atoll

While the Bikinians remained displaced on Kili, the rehabilitation project on their home atoll proceeded at a sluggish pace. According to one report, the equipment used for cleanup and construction purposes on Bikini was “in such poor condition that work had been slowed down.”99Close Since the United States had withdrawn its military personnel from Bikini, weekly air service between the atoll and Kwajalein had ended. This lack of air service, combined with a small number of boats—there were only three and all were in poor condition—meant that the agricultural and construction projects were behind schedule.100Close According to the Bikinians, the work done by the housing contractor selected by the TTPI government was sloppy and characterized by continuous delays.101Close

As a result of these ongoing problems, the Kili Council voted not to return the remaining islanders to the home atoll. By this time, though, three extended families had already moved back to Bikini Island and were living in some of the newly constructed houses.102Close But the radiological safety of these homes was in doubt. Based on a quick trip to the island, Dr. Martin Biles of the AEC wrote a favorable report, noting that “the reduction of radiation levels inside these houses meets our most optimistic estimates with inside levels half to one-third those outside.”103Close However, as the legal representatives for the Bikinians explained in 1973, “It is uncertain—in spite of AEC statements to the contrary—that residence there will be safe. There is still a question of radioactive danger, as evidenced by the fact that the AEC required four-inch concrete floors in the Bikini houses.”104Close

Despite the per sis tent evidence of contamination, the Department of the Interior reported that forty “model” houses had been built on Bikini Island and approximately eighty people were living in them. In addition, over 80,000 coconut trees planted on Bikini and Eneu islands were “beginning to reach bearing age.” Overall, about 50 percent of the rehabilitation program was completed by early 1974.105Close

In March of that year, researchers from the Brookhaven National Laboratory arrived to conduct examinations of the people who had resettled on Bikini Island. Led by Dr. Conard, these scientists examined the levels of radioactivity in the residents on Bikini using urine samples and whole-body counting.106Close As well, the scientists analyzed various food items and “general radiation on the island.” Afterward, Conard sent a very positive report to Oscar deBrum, the Marshallese district administrator. In this letter, the doctor reported that “the people living on Bikini have very low levels of radioactivity in their bodies” and the “radiation levels on the island are also low.”107Close

Despite Conard’s reassuring report, the AEC advised that a more sophisticated follow-up study be conducted by the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA), which had recently assumed AEC functions regarding Bikini. After receiving this recommendation, the Department of the Interior called a temporary halt to the resettlement and construction activities on Bikini.108Close In March 1975, the secretary of the interior, Roger Morton, wrote a strongly worded letter to the secretary of defense explaining that the ERDA was prepared to conduct a thorough radiological survey of Bikini in April if DOD would provide the necessary logistical and financial support. As Morton put it: “Since the situation has potentially serious political implications for the US government and the Administration [ERDA], I strongly request that you consider providing the necessary support from Department of Defense resources.”109Close

But, in May 1975, the DOD rejected Interior’s request for the support needed for the new survey.110Close Given the lack of cooperation from the DOD, combined with continued pressure from the Bikinians to resume the resettlement project, the ERDA conducted an intensive ground radiological survey of Bikini Island in June 1975, which resulted in some important discoveries.111Close In contrast to Conard’s positive conclusions, the ERDA reported that people living on Bikini Island might receive radiation exposures above acceptable standards depending on where they lived on the atoll and what foods they ate. Since exposure estimates for the people living in the interior of the island were the highest, the ERDA advised that no additional houses be built in that area. In addition, the report concluded that certain staple foods grown on the island, such as pandanus, breadfruit, banana, papaya, and coconut crabs, not be eaten. The ERDA also recommended that well water on Bikini Island be used for agriculture only.112Close The Department of Interior summarized the report:

In June 1975 an intensive ground radiological survey was conducted by the ERDA and it revealed that the original recommendations concerning resettlement on Bikini Island needed major revision. It became evident that the radionuclide intake in the plant food chain had been significantly miscalculated in terms of human consumption…. The survey demonstrated conclusively that the interior of Bikini Island should not be used for residential purposes; that well water should not be used for human consumption; and that locally grown food be placed on a restricted basis as far as consumption by the people is concerned.113Close

On 24 October 1975, the Bikinians’ legal counsels, George Allen and Ed King (both of the MLSC), met with Fred Zeder, the director of territorial affairs in Saipan. According to the lawyers, the Bikinians were very dissatisfied with Conard’s work: “The people have lost confidence in the doctor.” Based on the ERDA’s assessment in June, the islanders also had serious concerns about the radiation levels on their home atoll.114Close As a result, Oscar deBrum wrote a strong letter to the high commissioner recommending that the people be moved from Bikini Island to another island on the atoll with less radiation.115Close

In addition, the Bikinians sent a petition to the US Congress demanding a radiation survey of Bikini “at the earliest possible date.” They also requested in dependent scientific analysis of the survey once it was completed, in order to make informed decisions regarding their “future location and the homes for ourselves and our children.” If the scientists concluded that their home atoll was unsafe, the Bikinians wanted the United States to help them resettle elsewhere in the Marshall Islands. In addition, they demanded another $1.5 million in compensation for the approximately 500 people residing on Kili who needed money for food, housing, and other family expenses.116Close

The Bikinians’ concerns about the safety of their atoll were valid. By 1976, it was increasingly evident that living on Bikini Atoll was a health hazard. In September of that year, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) prepared a report for the ERDA that assessed the amount of plutonium in the bodies of the Bikinians who were residing on the atoll. Contrary to Conard’s assurances about the “low levels of radioactivity in their bodies,” urine samples taken annually from the Bikinians between 1970 and 1975 revealed significant increases in their body burdens of plutonium. Using a population in New York as a control group, the study found that the Bikinians had ten times as much plutonium in their bodies as the Americans. Although some of the plutonium was entering the bodies of the Bikinians through inhalation from the air and soil, most of it was being ingested from contaminated food and water on the atoll. Samples from food grown on Bikini, such as papaya and pig muscle, for example, had concentrations of plutonium 100 times larger than similar food products in the New York diet. Given the toxicity of plutonium and its tendency to reside in the liver, bones, and lymph nodes of humans, these findings were “cause for concern.” Nevertheless, the study of the Bikinians provided the United States with a unique opportunity to learn more about the “metabolism of plutonium in the body.” In 1976, the authors of the report concluded: “Bikini Atoll may be the only global source of data on humans where intake via ingestion is thought to contribute the major fraction of the plutonium body burden. It is possibly the best available source of data for evaluating the transfer of plutonium across the gut wall after being incorporated into biological systems…. It appears that the transfer across the gut wall of plutonium incorporated into food products is greater than previously expected.”117Close

Tests conducted by American scientists on Bikini in 1977 also revealed unsafe levels of other radionuclides on the atoll. As the acting director of territorial affairs, George Milner, explained in a report to the high commissioner regarding the “Health of the People of Bikini Island,” the level of radioactive strontium-90 in the well water of the island exceeded acceptable US standards. As well, a number of foods being consumed by the Bikinians, such as breadfruit, pandanus, and coconuts contained unsafe levels of cesium-137. The health of the islanders was at risk given “the recycling of radionuclides by the plant life” and the “higher intake [of radionuclides] by the residents who are eating local produce.”118Close

Despite these findings, Dr. Conard claimed that there was “no immediate danger to the present residents” on Bikini Island. While he recognized that the presence of available food on the island was “an irresistible temptation, especially in the children,” Conard recommended that the Bikinians cease eating all locally grown produce and instead rely on an “increased subsidization of food by the Administration.”119Close However, the Bikinians were increasingly uneasy about remaining on their island. Based on his experience as the BNL’s resident physician in the Marshall Islands, Dr. Konrad Kotrady reported in 1977 that “The people living at Bikini fear the ‘poison’ (radiation) that might be lingering on the island.” In particular, the islanders were concerned about the potential danger of secondary doses of radiation received from eating the local food, drinking the water, and living on the contaminated soil. According to Kotrady, the people failed to understand how Conard and the other scientists could know that “plutonium and other lingering radiation exists on the island such that some foods cannot be eaten, and then tell the people there is no danger.”120Close Some Bikinians were coming to the conclusion that they had been moved back to their island as “guinea pigs” so that American scientists could measure the long-term effects of human exposure to radioactive fallout during the Cold War.121Close

Despite the increasing health risks, the Department of Energy, which had replaced the Atomic Energy Commission in 1977, left the islanders on Bikini for another year. While this decision posed an obvious health hazard to the families living there, it provided the BNL with an opportunity to acquire more research data about the effects of human exposure to radioactivity. Of the approximately eighty people living on Bikini Island in 1977, thirty-four were children, aged twelve years and under.122Close

In April 1978, a US medical team from the BNL arrived to conduct examinations on the people living on the island.123Close Apparently still not understanding the full health risks involved, the Bikinians offered the American visitors coconuts as a sign of friendship. When the doctors completed their examinations of the islanders—using urine analyses and whole-body counting—they discovered “a continuing increase in body burdens of these radionuclides [strontium-90 and cesium-137] to levels that were considered unacceptable.”124Close In one year, the amounts of cesium-137 in the islanders’ bodies had risen 75 percent, leading the AEC doctors to conclude that “the Bikinians had likely ingested the largest amounts of radiation of any known population.”125Close

During a later interview, the health physicist in the AEC’s Division of Biology and Medicine, Gordon Dunning, admitted that the agency made a serious mistake when it declared Bikini Atoll safe for rehabitation in 1968. In estimating the dose of radiation that the resettled islanders would ingest by eating the food on Bikini, he argued, the AEC had relied on a 1957 report, based on the diet of the Rongelapese that assumed a daily consumption of only nine grams of coconut. According to Dunning, this was a gross error off by a factor of about one hundred. “We just plain goofed,” he told Weisgall.126Close

What Dunning failed to point out, however, was that a report completed by the AEC on the diet of the returning Enewetak population estimated a daily consumption of at least one hundred grams of coconut per person.127Close In addition, Dunning’s glib answer does not explain why the AEC failed to remove the Bikinians after the ERDA discovered high levels of radiation in the food and water on the atoll in 1975. Because of the studies conducted on the Bikinians between 1970 and 1975, the scientists knew that the body burdens of plutonium were steadily increasing. In addition, earlier studies conducted by Conard and the BNL researchers on the people of Rongelap clearly showed that the body burdens of cesium-137 and strontium-90 in that population increased once they were returned to their contaminated atoll. Given the available data from these studies,128Close it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Dr. Conard and his team utilized the Bikinians as research subjects during the period between 1970 and 1978.

Indeed, the BNL’s studies of both the Bikinians and the Rongelapese fit neatly into one of the “common and recurring” categories of human radiation experiments later identified by the Department of Energy. According to the department’s own definition, “All radionuclide metabolism studies in human subjects were considered as human radiation experiments. These tests involved the study or analysis of radioisotope uptake, retention, and excretion, and were done to learn more about the specific behavior of elements in the body.”129Close

Given the alarming levels of radionuclides in the bodies of the Bikinians, the Department of Interior finally decided to move them off their contaminated atoll. On 11 August 1978, Undersecretary James Joseph traveled to Bikini and offered to move the islanders back to Kili. Since the United States considered itself “generally responsible for the well-being of the Bikini people and their descendants,” it was willing to “arrange their relocation, permanently, in the most satisfactory manner possible.” Recognizing that the housing and other facilities on Kili were inadequate, the Americans were prepared to “undertake a program for the permanent rehabilitation” of the island. A new dispensary, school, and houses would be built on Kili and improvements would be made to the existing church and assembly hall. In addition, the United States agreed to give the Bikinians a onetime relocation allowance of $100.72, to be paid to the head of each family now on Bikini Island. However, the Americans wanted the islanders to understand that this sum was “not intended to constitute compensation, in whole or in part, for any damage the Bikini Island residents may be found to have sustained.” If the relocated Bikinians wanted to return to their home atoll, the Trust Territory government would arrange for brief visits from “time to time”; nevertheless, it was important for them to realize that Bikini Island “would not be fit for human habitation for decades to come.”130Close

The Ongoing Struggle for Justice

According to islander Emso Leviticus, “We were devastated when we had to evacuate Bikini in 1978. We were crying; it was a hopeless feeling.”131Close By late August, most of the 139 residents on Bikini Island returned to Kili but some moved to other islands, such as Ejit (part of the Majuro Atoll). As Charles Bussell, a Food Services Officer, reported, conditions on Kili remained extremely difficult:

The island is inhospitable by comparison to others, i.e. there is no lagoon, it is not capable at this time of producing sufficient food supplies to meet the needs of the persons living there regardless of income. There is no airstrip or dock for regularly scheduled shipping. From late November through March heavy seas and surf make supply logistics exceedingly hazardous. The people as a group are virtual prisoners of their environment. The sea is shark infested making traditional fishing—usually lagoon oriented—nearly impossible. Over the years the population has become totally dependent on USDA donated foods.132Close

In Bussell’s view, the Bikinians had become too reliant on Washington for food, a dependency fostered by their lawyers, and their “activities in the courts.”133Close Nevertheless, the pressure employed by the Bikinians’ legal counsel was effective in helping them win additional financial aid from the Americans. In recognition of the hardships faced by the islanders, the US government passed Public Law 95348 in 1978, adding $3 million to the Bikinians’ trust fund.134Close As well, the US Congress provided a $1.4 million ex gratia payment to the people of Bikini by Public Law 96-126.135Close

After the Bikinians were moved to Kili, Jonathan Weisgall, their legal counsel since 1975, filed a lawsuit in the US District Court in Hawai‘i demanding that the Americans conduct a full scientific survey of Bikini (and other atolls in the Northern Marshalls) to be completed “no later than December 31 of 1978.”136Close In response to this pressure, the United States signed a memorandum of agreement promising to complete the survey using “the latest and most effective technology, including aerial radiation surveying.”137Close As a result, the islanders dropped the lawsuit and the survey of Bikini was completed by the end of 1978.138Close Unfortunately, this survey concluded that Bikini Island was so contaminated that it would be off-limits for sixty to eighty years and Eneu Island for twenty to twentyfive years.139Close

Ironically, the people of Bikini regained legal control of their contaminated atoll after being moved back to Kili. On 24 January 1979, the new high commissioner, Adrian Winkel, executed a quitclaim deed granting the Bikinians the legal right to their home atoll (as well as Kili Island and parts of Jaluit Atoll). According to this document, “all rights, title and interest of the Government of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands including use rights” were released “unto the people of Bikini.”140Close

This quitclaim deed put the Bikinians in a curious position. They regained legal control of their home atoll, but due to the high levels of radiation, they were not able to live there. Dissatisfied with their situation, the islanders asked their legal counsel to put additional pressure on Jimmy Carter’s administration. As their lawyer, Jonathan Weisgall, explained in his correspondence with the Department of the Interior, the islanders had both immediate and long-term goals. In the short term, they requested an independent (non-US government) scientific review and assessment of the radiological survey, with emphasis on the conditions of Bikini and Eneu Islands. By this time, they had “lost all trust in US government scientists.” In the longer term, the islanders had four main objectives: continued monitoring and cleanup of Bikini; eventual resettlement on the atoll; future medical care; and additional monetary compensation. From the islanders’ perspective, the United States bore direct responsibility and liability for their short-and long-term injuries, losses, and needs.141Close

The Bikinians also made other demands. In 1980, the Bikini Council requested that representatives from the Department of Energy come to Kili and participate in a Dose Assessment Conference (as the Americans had done at Enewetak in 1979).142Close When the Americans arrived at this conference on October 8, they were greeted by protest signs that proclaimed “Welcome to Kili, Our Temporary Home” and “We wish no other home than Bikini.”143Close A number of US representatives from the Departments of Energy and Interior attended this two-day meeting, accompanied by their legal counsel and scientists from the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory and the Pacific Northwest Laboratory. Leaders from the Marshallese government, the Bikini Council, their lawyers, and numerous people from the Kili community were also in attendance.144Close During the conference, the US delegation presented the Bikinians with information in a booklet prepared by the DOE entitled “The Meaning of Radiation at Bikini Atoll.” According to this booklet, and the accompanying slide show, Bikini Island was still off-limits but Eneu might be habitable if the people followed proper guidelines, such as limiting their diet to 50 percent or less local food and agreeing to subject themselves to examinations by the Department of Energy.145Close

Perhaps not surprisingly, the Bikinians were not enthusiastic about this proposal. Given the recent official statements regarding the serious contamination on Eneu, Marshallese Senator Henchi Balos wanted to know why the Department of Energy was now suggesting that the Bikinians return to the island. Other islanders also asked questions. How much radiation already existed in their bodies due to the US testing program? What were the results of the examinations (whole-body counts and urine tests) done by the AEC in the 1970s? What would happen to them if they returned to Eneu? How contaminated was the island and what were the risks to their health? What if their children ate more food on the island than they were supposed to? If the island was safe, why was the DOE suggesting that they only eat some of the local food?146Close

In response, the DOE representatives provided answers that were not reassuring. Based on the studies of the Bikinians in the 1970s, the DOE had records regarding the amount of cesium-137 in the islanders’ bodies but these records were kept in the United States.147Close Of those islanders who had radionuclides in their bodies, there was a “small chance” that some would die from cancer in the future. For those Bikinians who chose to return to Eneu, these health risks might increase, especially if they didn’t follow the guidelines and chose to eat only local food on Eneu. Even if the Bikinians did not eat any food grown on the island, there were no guarantees regarding their health. As Dr. Bill Bair of the Pacific Northwest Laboratory explained, “It’s never 100 percent safe to live anywhere. On Eneu, even if you do not eat any food grown on the island, you still will inhale radioactive material from the dust you breathe.”148Close

Given the nature of the information provided by the DOE at the conference, it is understandable that the Bikinians felt uneasy about returning to Eneu. Many were suspicious about the Department of Energy’s motivations. They wondered why the DOE wanted to move them back to the contaminated island and then conduct examinations of their bodies.149Close Others highlighted their general lack of trust of the United States. One of the elder Bikinians put it this way:

I compare today’s meeting to the meeting we had when we were asked to leave Bikini originally. We were told by a person representing a country of great power to leave so testing could be done. We were afraid we would die if we didn’t leave. We were told we would be taken care of and watched over…. We went to Rongerik and were poisoned by fish…. We ended up here on Kili and were told we would be here until Bikini was safe and we would be told to return…. We are not happy here…. You brought us this book[let], I throw it down.150Close

Distrustful of the United States, the Bikinians decided that they wanted independent scientists to review the situation on Eneu before they made any decisions about returning. They also queried the Americans about compensation for the environmental damage caused by the nuclear testing program. Some asked about compensation for the destruction of several of their islands. As one Bikinian put it: “I wonder, since the bombs destroyed three islands, and they now no longer exist, do you plan to pay for those islands?”151Close

In reply, Gordon Law, the deputy assistant for the Department of Interior, contended that compensation was not “an Interior … legislative or moral obligation” for the United States.152Close In his opinion, “Historically money ruins societies, it does no good.”153Close Nevertheless, near the end of the conference, Law presented the Bikinians with $100 “as a small token,” in the hopes that it would “cause people to remember that a new era for the people of Bikini started here.”154Close

After the conference on Kili, representatives for the displaced islanders continued to present the Americans with requests. During a meeting with representatives from the Department of Interior, Senator Balos of the newly formed Republic of the Marshall Islands government repeated the Bikinians’ desire for independent scientists to review the environmental situation on their home atoll.155Close In several telegrams to the high commissioner, Balos also emphasized the ongoing food shortages and transportation difficulties faced by the Bikinians living on Kili and Ejit.156Close As the senator explained, “We did not voluntarily leave Bikini to come to Ejit. It was the US government who made us leave our beautiful shores and lands in Bikini atoll and brought us to a stranger’s lands on Ejit [in 1978]. Why doesn’t the US government live up to its obligations and responsibilities toward Bikinians? Is it because there are only hundred people out here, who gives a damn? If that’s so, take us back to Bikini atoll where we belong. We’d rather die on Bikini than be suffered [sic].”157Close

In early 1981, the Bikinians’ legal counsel sent a letter to the high commissioner outlining the islanders’ major grievances against the Americans: their removals from Bikini in 1946 and 1978, their suffering and hardship since 1946, the destruction of certain islands in their atoll, and various breaches of fiduciary responsibilities by the US government.158Close Based on these complaints, the Bikini Council instructed Jonathan Weisgall to file a class action suit against the United States. By this time, the council was persuaded that litigation was the most effective way to force Washington to provide them with the monetary compensation they deserved. Their lawsuit sought compensation under the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution for the taking of their atoll (in 1946 and 1978).159Close They also sought redress for the American government’s “repeated and continuing breaches of fiduciary duties” which had resulted in “severe physical, emotional, and financial injuries.” In total, the Bikinians demanded that the US government pay compensation not less than $450,000,000.160Close

The plaintiffs named in the petition were all members of the Bikini Council, but the suit was filed on behalf of all living persons who were members of the Bikini community prior to the 1946 evacuation and their descendants. At the time, over 990 members of the Bikini community—most lived on Kili and some on Ejit—were considered part of this case. According to their legal counsel, the people of Bikini chose a class action approach because it permitted “numerous injured persons to prosecute their common claims jointly in a single forum” and thus avoided unnecessary duplication.161Close When a reporter from the Marshall Islands Journal interviewed Weisgall, the lawyer drew parallels between the Bikinians’ lawsuit and cases fought by Native Americans in the United States.162Close

Although the Bikinians’ lawsuit was unsuccessful, the pressure brought by the islanders did have an impact on the US Congress. In 1982, Congress voted in favor of a trust fund for the Bikinians under US Public Law 97-257; according to the terms of this legislation, entitled “The Resettlement Trust Fund for the People of Bikini,” the islanders were granted $20 million.163Close Later, the US government passed additional legislation, Public Law 100-446, providing $90 million for the cleanup of Bikini and Eneu Islands of the Bikini Atoll.164Close

While this legislation was being considered by the US Congress, representatives from the Republic of the Marshall Islands and the United States were engaged in negotiations regarding the Compact of Free Association. In September 1983, a majority of Marshall Islanders (58 percent) voted in favor of this agreement with the United States. Under the compact, the Americans were granted full authority for all defense matters in the Marshall Islands, including the right to use Kwajalein Atoll as a missile testing base. In return, the Marshallese were given self-government and additional financial assistance from the United States. The Bikinians, however, were not party to the negotiations that led to the compact or the related Section 177 agreement,165Close and 79 percent of them voted against it.166Close At the time, the Bikinians realized that the amount of money offered by Washington would not provide sufficient compensation for the extensive health and environmental damages caused by the nuclear testing program.

Following approval of the compact in 1986, the United States created a fund that disbursed money to the four Marshallese communities whose atolls were most affected by nuclear tests (Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap, and Utirik). From this fund, the Bikinians received a $75 million trust, with a yearly disbursement of $5 million over 15 years.167Close As a condition of this trust fund, however, the Bikinians—like other islanders—were required to terminate any pending legal cases against the United States related to nuclear testing.168Close

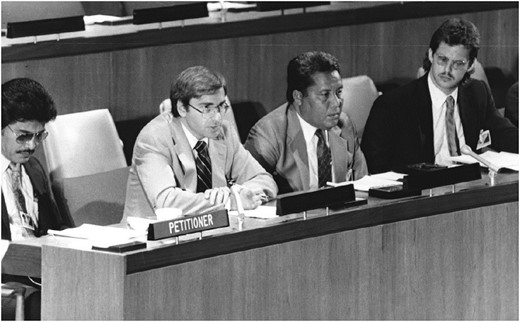

Although the Bikinians could no longer file lawsuits in the United States, they continued to draw international attention to the problems caused by the nuclear testing program. In 1988, a delegation from the Marshall Islands gave testimony

Senator Henchi Balos, legal counsel Jonathan Weisgall, Mayor Tomaki Juda, and liaison Jack Niedenthal testifying at the UN in 1988.

at the United Nations regarding the ongoing challenges involved in the cleanup and resettlement of Bikini Atoll.

That same year, the Bikinians sent letters to various Americans inviting them to “Bikini Day,” an annual event held on Kili to commemorate their displacement. As the invitations explained, the celebration on Kili marked “42 years of exile from our homelands … and ten years since we discovered the true extent of the damage done to our islands by the nuclear tests.”169Close On March 11, the islanders and their guests enjoyed music, dancing, food, and speeches by prominent Bikinians. Iroij Kotak Loeak said that he shared the sorrow felt by the Bikinians who lived on Kili. “There’s no place better than home,” he stated. Nitijela Speaker Kessai Note thanked all of the Bikini leaders who had tried to make life better on Kili. As he put it, “The advances of the Bikini people have come from the people themselves.” Senator Henchi Balos emphasized the community’s wish that the US Congress continue to provide necessary funding for the cleanup and rehabilitation of Bikini. As a sign carried by a young Bikinian declared, however, “There are miles to go and promises to keep.”170Close

In keeping with one of these promises, the United States supported the creation of the Nuclear Claims Tribunal (NCT) on Majuro in 1988. Once the tribunal was established, the Marshallese affected by the nuclear tests began to make individual claims. Mr. Leviticus, for example, filed a personal injury claim after his son, Dial, died of a “very aggressive lymphoma.” Dial was one of the young children who returned to Bikini Island with his family in the 1970s. During the two years and three months that he lived on the contaminated island, he was exposed to an excessive amount of radiation. After reviewing the evidence presented by experts in this case, the NCT concluded that Dial’s family should be given an award since there was a direct connection between his exposure to radiation on Bikini Island and the onset of the lymphoma that killed him prematurely at age eleven.171Close

In addition to individual claims, the People of Bikini filed a class action claim with the NCT in 1993 seeking damages resulting from the consequences of the US nuclear testing program. Based on this claim, the tribunal held several hearings, reviewed thousands of pages of documents and reports, listened to arguments from expert witnesses and lawyers, and heard testimony from the Bikinians themselves. During the deliberations for this case, the defendants went to great lengths to minimize the problems caused by the American program.172Close Eventually, though, the NCT was more convinced by the evidence provided by the witnesses speaking on behalf of the islanders. In 2001, the Tribunal concluded that the Bikinians should be granted a total award of $563,315,500: $278,000,000 in compensation for loss and use of their atoll; $251,500,000 for the cleanup and restoration of Bikini;173Close and $33,814,500 for the hardships suffered during their long exile. The NCT concluded:

The process has been a long and difficult one as the Tribunal has grappled with many issues in need of resolution in the decision process. However, none of what has transpired before the Tribunal can begin to compare with the stark reality that the People of Bikini have remained in exile for some 55 years now. Although the Tribunal has determined that the people of Bikini have suffered loss and injury to person and property, nothing can compensate for that simple fact and all of the attendant intangible damage, loss, and hardship suffered by the Bikini community over the years. In this respect, the Tribunal hopes this award will help bring closure to this tragic legacy, and allow the Bikini community to move forward empowered to make their own future.174Close

In the end, however, the United States did not adequately fund the NCT and the Bikinians (like the Enewetakese) only received a small fraction of the award granted by the tribunal. Although small initial payments were made to the Bikinians (totaling $2,279,179.83), they represented less than one-half of one percent of the total award. Since Washington failed to provide any further payments, the Bikinians filed a case with the US Court of Federal Claims. When that case was dismissed on appeal, the Bikinians sent a petition to the US Supreme Court, but it was denied on the grounds that the Marshall Islanders gave up their right to pursue claims in the United States once they signed the Compact of Free Association.175Close