Kua'aina Kahiko: Life and Land in Ancient Kahikinui, Maui

Kua'aina Kahiko: Life and Land in Ancient Kahikinui, Maui

Contents

Cite

Abstract

This chapter describes the formation of the Kahikinui landscape. The land of Kahikinui was formed of endless lava outpourings that cascaded for tens of thousands of years from the craters and cinder cones that gash and dimple the slopes of Haleakalā. More than anything, Kahikinui is a land of lava, congealed after the fiery flows scorched everything in their path. Far from being monotonous, Kahikinui exhibits significant differences between its older eastern and younger western regions. These differences reflect a quarter of a million years of geological time over which Pele sent down countless lava flows. Meanwhile the inexorable forces of wind and water simultaneously transformed the ʻaʻā and pāhoehoe surfaces into landscapes that the Polynesian colonizers of Kahikinui were to inhabit and farm.

Lying astride the southern flank of Haleakalā, the land of Kahikinui was formed of endless lava outpourings that cascaded for tens of thousands of years from the craters and cinder cones that gash and dimple that great mountain’s slopes. More than anything, Kahikinui is a land of lava, congealed after the fiery flows scorched everything in their path. To understand this land—and how a Polynesian people made their living off its often harsh and challenging features—we must begin with the underlying geology.

Haleakalā, like all Hawaiian volcanoes, originated from a hot spot, or plume of magma originating deep within the earth’s mantle. Haleakalā and East Maui began to form about 2 million years ago; by 200,000 years ago, the mountain had achieved its current height, 3,055 meters above the sea. Even before its volcanic fires became dormant, massive collapses created the distinctive summit caldera. Erosion from wind and rain then carved two great gashes into the mountain’s sides—the Ko‘olau and Kaupō Gaps. Smaller valleys and ravines began to form, dissecting the originally continuous surface of lava flows. Yet Pele had not finished her work. She continued to send lava flows cascading down the mountain slopes, emanating from the long rift zones extending southwest and northeast from the summit to the coasts (see fig. 10). The last of these flows occurred between A.D. 1439 and 1633, building a promontory of black lava defining one side of La Pérouse Bay, Keone‘ō‘io. To this day, Pele has not entirely abandoned Maui; geologists predict that more lava flows will yet spew forth from the rift zones at some future date.

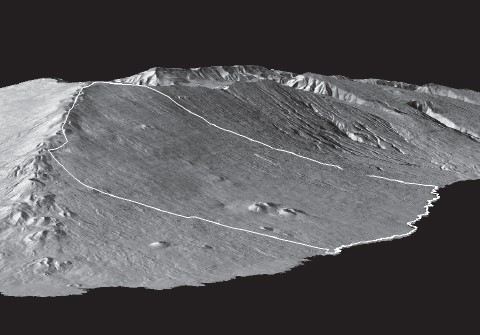

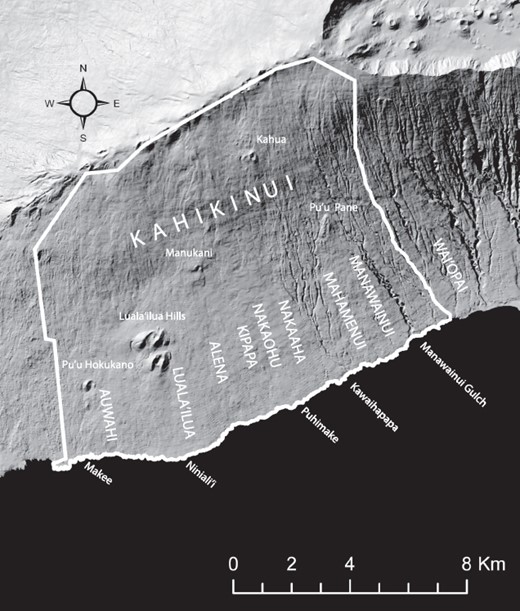

Digital elevation view of southeast Maui with the district of Kahikinui outlined in white. The prominent cinder cones in Kahikinui are the Luala‘ilua Hills. The great crater of Haleakalā and Kaupō Gap can be seen beyond Kahikinui.

Modern understanding of Maui’s geology began with the pioneering fieldwork of Harold T. Stearns. From 1932 to 1942, Stearns traversed the island’s ridges and valleys, mostly on foot or horseback, mapping the different lava flows and cinder cones with the assistance, toward the end of this formidable task, of Gordon A. Macdonald. The team produced the first detailed account of Maui’s geology, accompanied by a splendid color map. For East Maui, Stearns and Macdonald divided the landscape into three “volcanic series,” stacked one upon the other like a giant layer cake. The oldest and deepest of the layers is the Honomanu

series. This can be glimpsed in only a few deep gulches on Maui’s windward side, where erosion has sliced open the mountain, exposing the rocks that first built up the Haleakalā shield. Next came the Kula series, with lava flow after lava flow relentlessly building the mountain higher and higher. After the Kula series ended, Stearns and Macdonald believed that there was a “great erosional unconformity,” a period when the lava flows ceased and the work of wind and water cut gulches and valleys into the slopes of the great mountain. We now know that the outpourings of lava did not entirely stop during this phase, but merely slowed down, allowing erosion to gain the upper hand over mountain building. After a time, Pele renewed her efforts and the final Hāna series of lava flows began to spew forth from the long rift zones cutting across the mountain. The Hāna flows plastered the mountain’s surface over large areas (especially in Hāna district), filling in the eroded gulches and rejuvenating the landscape (see fig. 11).

The land of Kahikinui as seen from Pu‘u Kahua at an elevation of 2,172 meters above sea level. Note how the eastern part of Kahikinui (to the left in the photo) is dissected by deep gulches, whereas the western part is covered in more recent lava flows.

When I began to study Kahikinui in 1995, I consulted the classic work of Stearns and Macdonald. One day, not long after we had started our archaeological reconnaissance across the uplands of Kīpapa, I spied in the distance a figure hiking across that forlorn landscape. He clearly was not a local pig hunter; I guessed he could only be another scientist. Hailing him from across a shallow gulch and then hiking over to see what he was up to, I met Eric Bergmanis, a University of Hawai‘i graduate student conducting fieldwork for his master’s thesis. Following in the tradition of Stearns, Bergmanis was walking

the land, back and forth, carefully mapping where one lava flow stopped and another began. But Bergmanis was armed with more sophisticated tools than Stearns had had at his disposal: a GPS receiver to map his position precisely, and—back at the UH laboratory—a mass spectrometer that could measure the chemical composition of his rock samples in parts per million.

My discussions with Bergmanis—and later reading of the results of his research—helped me to understand how the Kahikinui landscape had been formed. To the casual visitor who drives through Kahikinui on the single, narrow road from west to east, all might appear a monotonous succession of lava slopes punctuated by a few looming cinder cones. But for those of us who have spent countless days hiking over these lands, the topography of Kahikinui is endlessly varied.

Each time I go to Maui to continue my field studies, I first pick up my trustworthy Jeep from my friends Ray and Shiela in Haiku (its four-inch lift job allows

me to traverse the most torturous four-wheel tracks in the district). Loading the now aging but always reliable Jeep with supplies and ice, I drive the winding Pi‘ilani Highway toward ‘Ulupalakua Ranch, stopping at Ching Store in Kēōkea to top off my gas tank. There are no stores, no gas stations, past Kēōkea until one gets all the way to Hāna. Florence Ching has run her store since well before I can remember. She always greets me the same way: “Oh, Patrick, you’re back again working in Backside?” It amuses me how the ancient Hawaiian kua‘āina, “back of the land,” continues in local parlance as “Backside.” This is what Ching and others call the lands stretching beyond ‘Ulupalakua to Kaupō and Kīpahulu.

Leaving Kēōkea, I admire the splendid view of Kaho‘olawe Island, along with the more distant Lāna‘i. I pass through the tiny hamlet of ‘Ulupalakua perched on Haleakalā’s southwest rift zone, rounding the cinder cone of Pu‘u Māhoe. The road now faces due east and the incredible sweep of Haleakalā’s massive southern flank suddenly comes into full view. What appears on the island map as the “Pi‘ilani Highway” now narrows to just two lanes with no shoulder, asphalt having been poured down over an older dirt road, which itself followed the track of the ancient foot trail from ‘Ulupalakua to Hāna. Driving through Kanaio I admire the looming cinder cone of Pu‘u Pīmoe on the right; within a few minutes I will enter the lands of Kahikinui.

Approaching Kahikinui from the west, I cross the ancient moku boundary at Auwahi, an ahupua‘a belonging to ‘Ulupalakua Ranch but originally part of the district (see map 2). It was one of the many estates of the high chiefess Ruth Ke‘elikōlani, granddaughter of King Kamehameha I, awarded to her during the Great Mahele. Auwahi is made up of overlapping flows of the Hāna volcanic series, massive ‘a‘ā lavas with intermingled pāhoehoe, forming a distinctive topography of low ridges broken by shallow depressions. Like a giant angry pimple, the reddish cinder cone of Pu‘u Hōkūkano rises above these flows. The pu‘u had some sacred significance to the ancient inhabitants of Kahikinui, for on its summit I have found pieces of branch coral, typically placed as offerings on the altars of Kahikinui heiau.

Continuing eastward, I now enter Luala‘ilua, an ahupua‘a dominated by the most dramatic geologic features in the entire district, a cluster of three massive cinder cones with several pit craters. The lava fountains that created these huge heaps of reddish-brown cinder and ash must have been spectacular, no doubt rising hundreds of feet into the air. Pockets of cinder and ash from their eruptions can be found over much of Kahikinui.

The Luala‘ilua Hills provide the setting for a number of legends, including that of a cannibal ogre who entrapped passersby on the trail from Hāna to ‘Ulupalakua, until he was tricked and sent plunging to his death in the pit crater by a young woman whose father had been one of the ogre’s victims. I heard this tale from the Reverend Ka‘alakea in 1997. One can see how these looming pu‘u might inspire such tales. In the early morning, and again in the late afternoon, the cloud bank that hovers along the upper slopes of Haleakalā often descends, enshrouding the Luala‘ilua Hills in swirling mist.

The narrow road skirts the base of the Luala‘ilua Hills. I always anticipate the spectacular view eastward across the lands of Alena and Kīpapa, the core of Kahikinui moku, which greets me as the road turns abruptly to descend along the steep slope of the pu‘u. About 3 kilometers away on a prominent ridge, one can discern the ruins of St. Ynez Church, where Thérèse and I encountered Kawaipi‘ilani Paikai of Ka ‘Ohana o Kahikinui in 1993. In the farther distance is the point of Ka Lae o ka ‘Ilio, the Cape of the Dog, in Kaupō, where the armies of Kalani‘ōpu‘u and Kahekili once clashed among the verdant sweet potato fields.

I continue eastward across the rough ‘a‘ā lava of Alena, dotted with ‘ōhi‘a and olopua trees. A mere 10,000 years old, this is the youngest part of the Kahikinui landscape. Beyond Alena lies Kīpapa ahupua‘a with its somewhat older terrain (about 52,000 years old); this greater age and weathering made Kīpapa’s lava flows highly suitable for sweet potato and dry taro farming. Alena and Kīpapa exhibit the ridge-and-swale topography typical of the young Hāna volcanic series.

At the prominent ridge in Kīpapa called Pu‘u Ani‘ani—where the ruins of St. Ynez chapel lie—I often pause to admire the sweeping view eastward, across the lands of Nakaohu and Nakaaha, and beyond to Mahamenui and Manawainui. From this vantage point in the late afternoon I can almost guarantee that I will see rainbows over Kaupō, where the misty rains of Kīpahulu blow out over the ocean at Mokulau. From Pu‘u Ani‘ani the road descends steadily, from about 370 meters above the ocean at St. Ynez to sea level at Kahikinui’s eastern boundary of Wai‘ōpai.

Leaving Pu‘u Ani‘ani and the ruins of St. Ynez, I pass two narrow, decaying concrete bridges crossing Kamole and Kepuni Gulches (see fig. 12). These deep slashes in the Kahikinui landscape were eroded by periodic flash floods that occur when winter, kona storms slam into the southern face of Haleakalā, unleashing torrents of rain. It was gulches like these that convinced Harold Stearns that a “great erosional unconformity” had occurred between the Kula and Hāna volcanic series. In fact, these gulches mark a major geological boundary within Kahikinui moku, with the younger Hāna landscape behind, to the west, and the older Kula volcanic series landscape to the east.

Kepuni Gulch is one of the deeply incised drainages in the eastern part of Kahikinui, where the landscape is of the geologically older Kula volcanic series.

In 2001, when I brought an interdisciplinary team of scientists to Kahikinui to try to understand how the ancient Hawaiians had managed to productively farm this arid landscape, we wanted to know how much older this eastern part of Kahikinui, with its Kula volcanic series, was than the western part with its Hāna series ‘a‘ā flows. Dave Sherrod of the U.S. Geological Survey had begun to work in Kahikinui at this time and had joined our group. Standing more than six feet, with a dark bushy beard and piercing eyes, Dave is a true field geologist, more at home sleeping under his beat-up Scout four-wheel truck than in a hotel room. Sherrod picked up where Eric Bergmanis had left off, mapping the ancient lava flows of Kahikinui and dating as many of them as possible to develop a fine-grained chronology of the Kahikinui landscape.

“Dave,” I shouted into the wind as we stood one day on the rim of Manawainui Gulch, plunging 60 meters straight down just past my boots, “do you think we

could get a sample of the last lava flow that formed this surface we’re standing on?” I was collaborating at the time with a geochronologist, or specialist in rock dating, Warren Sharp of the Berkeley Geochronology Center, whose lab can run potassium-argon dates on lava rocks. I thought that if we could get a sample of the last lava flow that had built up the surface of Manawainui ahupua‘a—clearly the oldest part of Kahikinui—we would be able to bracket the entire history of landscape formation across the moku.

“We’re at just the right place to do that, Pat,” Dave answered, pointing to the road cut ahead of us where the “highway” descends down into Manawainui Gulch. Years ago, when the road was blasted out of the basaltic rock, the core of the last ‘a‘ā lava flow had been exposed right at eye level. Dave strode over to his Scout and began digging into a canvas bag of equipment. I thought he must be searching for some high-tech sampling instrument but instead he emerged with a well-worn sledgehammer with a three-foot-long ash handle.

“Stand back! This sucker may let fly some nasty chips that could penetrate your eye,” Dave warned. Aiming the sledgehammer at the blue rock face, Dave slammed it into a protruding ledge. Sharp-edged chunks of basalt went skidding across the road. I picked up several shards and put them into a cloth sample bag, noting the GPS coordinates and date. A couple of months later, Warren Sharp e-mailed me the results of his potassium-argon dating of the rock that Dave’s sledgehammer had blasted off the road cut at Manawainui: 226,000 ± 4,000 years before present. As I will describe in chapter 8, this was an important advance in our understanding of Kahikinui’s geology and landscape, with implications for how the ancient Hawaiians had utilized this land.

Thanks to the dedication of field geologists such as Harold Stearns, Eric Bergmanis, and Dave Sherrod, we can now appreciate the subtle variations across the vast landscape of Kahikinui moku. Far from being monotonous, Kahikinui exhibits significant differences between its older eastern and younger western regions. These differences reflect a quarter of a million years of geological time over which Pele sent down countless lava flows. Meanwhile the inexorable forces of wind and water simultaneously transformed the ‘a‘ā and pāhoehoe surfaces into landscapes that the Polynesian colonizers of Kahikinui were to inhabit and farm.

From Manawainui, the rough road descends steadily toward the sea. Hot, dry air rushes through the Jeep windows, stinging my eyes. The land undulates gently, punctuated here and there by shallow stream channels. I note that there is far less rock on the landscape. All of this reflects the older topography, one that has been softened and mellowed by time. Manawainui Gulch is today the eastern boundary of Kahikinui, where the lands controlled by the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands end. But I continue on, reaching the ocean at the mouth of Wai‘ōpai Gulch. Here I pull the Jeep over at the rocky beach. Standing on the basalt boulders and cobbles rolled round and smooth in the crashing surf, with the salt spray in my face, I look out across the notoriously rough ‘Alenuihāhā Channel, toward Kohala district on Hawai‘i Island. Wai‘ōpai was originally within Kahikinui moku, although today it is a part of Haleakalā Ranch. In fact, historical research indicates that the ancient eastern boundary of Kahikinui was about 1.4 kilometers further east, at Pāhihi Gulch.

I am tempted to continue driving eastward, into Kaupō and Kīpahulu, entrancing landscapes in their own right. Indeed, in recent years my students and I have begun archaeological research in Kaupō. But that story must be left to another time.

The ancient Hawaiians called Kahikinui an ‘āina malo‘o, referring to the arid lands found on the leeward sides of the main islands. Malo‘o means “dried up, evaporated, juiceless, dessicated.” It implies drought and dehydration. The aridity of the leeward sides of the Hawaiian Islands derives from unique atmospheric conditions created when the dominant trade winds descending from the northeast meet the islands’ volcanic masses. Rising abruptly over the land, the moisture-laden oceanic air creates a meteorological phenomenon known as “orographic precipitation.” As a result, the islands’ windward slopes are more often than not blanketed with rain, sometimes reaching more than 3,500 millimeters of rainfall annually. This rain feeds the streams that Hawaiian farmers in the windward valleys tapped to irrigate their taro fields. By the time these winds have crested the mountain peaks, however, most of their water content has already been wrung out. This leaves the leeward regions, especially in the lower elevations, with little rain. In fact, the trades sweeping down the leeward slopes have a drying effect, as they actually increase evaporation. Hence the parched—the malo‘o—appearance of many leeward Hawaiian landscapes.

Kahikinui carries this leeward pattern to an extreme, because the huge mass of Haleakalā effectively blocks the trade winds entirely. The trades are forced around Haleakalā to the west and east. At the eastern end of Maui, Hāna district is the beneficiary of most of the orographic rainfall, with as much as 6,096 millimeters falling on its upper slopes. By the time the trades reach Kaupō, they deliver only about 1,500 millimeters of rain annually. The intensity of the wind blasting into Kahikinui does not die down—as the famous La‘amaikahiki himself experienced—whistling across the lava terrain in gusts of 20 to 30 miles per hour. But this air flowing across Kahikinui carries almost no moisture; it dries your skin and stings your eyes as you lean into it, struggling to keep your balance against the gusts.

Rainfall in Kahikinui comes not with the prevailing trades, then, but with the intermittent kona, or southerly storms, which occur primarily during the winter months between October and April. These storms form as subtropical depressions that move slowly eastward across the archipelago from the northwest, pushing southerly winds before them. The number of kona storms varies from year to year, from none in some years to as many as five or more in others. In Kahikinui, kona storms drop on average of between 500 and 1,000 millimeters of rain each year across the mountain slopes, less near the coast, and greater amounts farther inland. Because this rain is concentrated during the winter, ancient Hawaiian farming in Kahikinui was a highly seasonal affair. It was also risky, because a year or two without any kona storms brings severe drought. In my seventeen years of working in Kahikinui I have already witnessed two such droughts. During these periods the vegetation shriveled up, the land turned brown, and dust blew everywhere. I have shuddered to think of what it must have been like to have been a maka‘āinana farmer during such times.

There is, however, a second source of moisture providing life-giving water to the Kahikinui landscape: this is the “fog-drip precipitation” that occurs on the mid-elevation mountain slopes, mostly between 900 and 1,800 meters above sea level. This fog drip results from a temperature inversion layer that usually forms daily at an elevation of around 1,800 meters across the slopes of the higher Hawaiian mountains, including Haleakalā. The inversion layer is marked by a relatively shallow band where temperature increases—rather than decreases as usual—with elevation, keeping the cooler air below the inversion from rising. In the early morning and late afternoon, the summit ridgeline of Haleakalā is typically cloudless, standing exposed in full view across Kahikinui. But by midday a thick cloud bank develops below the inversion layer. This cloud bank consists of a “well-mixed marine air layer with abundant water vapor and suspended particles of sea salt,” as two Hawaiian meteorologists describe it. The cloud bank rarely produces actual rainfall. But as the damp, foggy air circulates through the dryland forest of koa and ‘ōhi‘a trees, water droplets form on the leaves of the trees and shrubs, steadily dripping off and seeping into the rocky, porous soil. In the days before cattle ranching, when the upland forests were more luxuriant, this fog-drip precipitation was a significant source of groundwater, traveling underground through the porous rock to feed seeps and springs at lower elevations (see chapter 12).

To round out the sense of life in the ‘āina malo‘o of Kahikinui, we need to consider the region’s biota—the native plants and animals that colonized this land over tens of thousands of years, as well as more recent invaders from foreign lands. The vegetation of modern-day Kahikinui has been irrevocably changed by the effects of cattle ranching and introduced goats, not to mention exotic plants such as lantana (Lantana camara) and the fast-growing glycine vine (Neonotonia wightii), which now run rampant over large parts of the landscape. Nonetheless, Kahikinui is still home to many unique species of endemic and indigenous Hawaiian trees, shrubs, herbs, and grasses. The uplands of Auwahi were a favored locality for the pioneer botanist Joseph F. Rock, who wrote that “not less than 60 percent of all the species of indigenous trees growing in these islands can be found and are peculiar to the dry regions or lava fields of the lower forest zone.” It is thanks to Rock and others who followed in his path—including botanist Art Medeiros, who has fought to preserve what remains of the Kahikinui dryland forest today—that the botanical richness of this region can be appreciated.

As everywhere in the islands, the biota of Kahikinui is strongly “zonated.” By this we mean that the plant and animal communities change markedly with elevation above sea level. To appreciate this zonation, let me retrace the route of our imagined journey from Wai‘ōpai back up the Kahikinui slopes into the higher elevations. Driving along above the sea cliffs toward Manawainui Gulch, I pass through what Hawaiian botanists describe as “coastal dry grasslands and shrublands.” Here the native ‘ilima (Sida fallax) with its beautiful yellow flowers forms creeping mats over the rocky soil. ‘Akoko (Chamaesyce skottsbergii) is another native plant found in this zone, whose wiry branches were used as fuel in ancient Hawaiian hearths. We often select ‘akoko charcoal for radiocarbon dating of ancient sites in Kahikinui. Salt-tolerant grasses such as ‘aki‘aki (Sporobolus virginicus) and kāwelu (Eragrostis variabilis) are common in the coastal zone. In ancient times, it is likely that the native pili grass (Heteropogon contortus), used as a primary thatching material for Hawaiian houses, grew luxuriantly after the winter kona rains. Unlike in many leeward areas, however, the invasive kiawe tree (Prosopis pallida) is rare in Kahikinui; in fact, there is a striking absence of any shade-giving trees along the windswept Kahikinui coastline.

Exiting deep Manawainui Gulch, the road climbs steadily uphill, diagonally along the volcanic slopes. Soon the open stretches of coastal grasslands are replaced by dry shrublands. Thickets of wiry ‘a‘ali‘i shrubs (Dodonaea viscosa) flourish in the lee of rocky ridges. Then I catch a glimpse of wiliwili (Erythrina sandwicensis), one of the most peculiar and intriguing of the Hawaiian dryland forest trees (see fig. 13). The soft, light wood was prized for the outrigger floats of Hawaiian canoes. Unlike most Hawaiian trees, wiliwili is deciduous, dropping its leaves in the fall and then flowering in the spring before the new leaves appear.

Wiliwili trees in Auwahi. These hardy, deciduous trees, which flower when the leaves have dropped, are characteristic of the ‘āina malo‘o of Kahikinui.

I never tire of gazing at the wiliwili of Kahikinui, with their amazing ability to grow right out of lava rocks. Their gnarled, orange-colored trunks contrast starkly with the black lava. In recent years the wiliwili stands of East Maui were decimated by an invasive gall wasp, although they are showing signs of a tentative recovery. But I still recall during my first years of fieldwork in Kahikinui when dense stands of wiliwili in the mid-elevations would burst into flowers of varied red, orange, and light-green hues around March or April. A Hawaiian proverb cautions, “When the wiliwili tree blooms, the sharks bite” (Pua ka wiliwili nanahu ka manō). To nā kua‘āina, there may have been a hidden meaning for this proverb, for the Hawaiians of old compared their chiefs to sharks. The spring flowering of the wiliwili corresponds with the end of the Makahiki, when the commoners owed their tribute to the chiefs, offered up in the name of Lono. If the tribute was considered inadequate, the chiefs and warriors would plunder the land. Hence the warning, “the sharks bite.”

To explore the higher elevations and their distinctive vegetation zones, we need to leave the main road. In Kīpapa, a short distance to the west of Pu‘u Ani‘ani, I turn off at the entrance to the Hawaiian Home Lands resettlement area, where the members of Ka ‘Ohana o Kahikinui have now claimed the legacy that Prince Kūhiō once promised to the Hawaiian people. Passing through

a locked gate, the dirt road winds steadily uphill. Stands of wiliwili are still common at this elevation, but other native trees and shrubs now join them, including sandalwood, or ‘iliahi (Santalum freycinetianum), the ‘ohe tree (Reynoldsia sandwicensis), which like the wiliwili is deciduous but taller and more stately, and the native olive, or olopua (Nestegis sandwicensis), whose hardwood was prized for adz handles. Commonly growing among these trees is the tough ‘ākia shrub (Wikstroemia spp.). Slightly higher, at around 750 meters elevation, a magnificent stand of the increasingly rare halapepe still thrives; this is an endemic Maui species (Pleomele auwahiensis). According to Joseph Rock, a halapepe forest once wrapped completely around the southeast Maui slopes from Kahikinui to Kula.

Before the arrival of humans, these marvelous dryland forests were inhabited largely by insects and diminutive land snails, most of which are now extinct. In Auwahi I have found the tiny shells of amastrid, tornatellinid, helicinid, and other endemic Hawaiian land snails preserved by the thousands in sediments that were washed off the upland slopes after Hawaiian farmers first began to burn and clear the area for gardens. The only vertebrates prior to humans were birds and a few bats, but we have only scraps of evidence of them from Kahikinui. In January 2012, I excavated a 3-meter-deep backhoe trench into sediments that had accumulated against the mauka side of Pu‘u Hōkūkano in Auwahi. Near the bottom on this trench we found the bone of a flightless ibis (Apteribis sp.), a hint of the rich birdlife that once roamed these dryland forests. When the Polynesians arrived, they introduced pigs, dogs, and fowl, all of which were raised as food animals. Little Pacific rats (Rattus exulans), as well as the house gecko, or mo‘o (Lepidodactylus lugubris), also came along with the Polynesians.

The zone from 300 up to 900 meters above sea level was, as I explain in chapter 8, the most intensively settled and heavily cultivated by the Native Hawaiian population. Most of the plants brought by the ancient Polynesians to Hawai‘i and cultivated by them—including sweet potato and taro—do not survive in the wild and have long since disappeared from the landscape. But in places I have come across old plants of kī (Cordyline fruticosa). This Polynesian introduction was prized not only for its starchy root (which when cooked in an earth oven produces a sweet, sugary substance that was mixed with taro to make kūlolo), but also for its waxy leaves, used to wrap fish for baking, make rain capes, and even fashion sandals. The kī plant also has sacred connotations; one gnarled, massive kī still grows out of the terraced face of a kahua platform in upland Nakaohu. Another Polynesian introduction that survives in the shady gulches of Kahikinui is the candlenut tree, kukui (Aleurites moluccana). The oily kukui kernel was ignited in stone lamps after dark to light the houses of nā kua‘āina and also served medicinal and culinary purposes. Here and there throughout the mid-elevations of Kahikinui one encounters the beautiful light-green foliage of kukui trees. Always they are situated in gulches or ravines, which offer protection from the incessant winds and where their roots can tap sources of underground moisture.

By now my Jeep is traversing the rugged four-wheel track winding up the eastern edge of Manukani, a cinder cone whose summit stands at 1,113 meters above sea level. The remnants of dry forest with wiliwili, ‘ohe, olopua, and halapepe have disappeared. The terrain is mostly blanketed with a dense mat of invasive Kikuyu grass (Pennisetum clandestinum), introduced from tropical Africa for cattle feed. But visual clues that this was not always so are unmistakable in the form of dead trunks and stumps of large trees; I make these out to have been koa (Acacia koa) and ‘ōhi‘a (Metrosideros polymorpha), two of the most important trees of the upper dryland forests. At one time in the not-too-distant past—certainly before the herds of cattle introduced by Pico in the 1870s began to maraud across the land—a luxuriant forest had extended down to this elevation.

I drive the Jeep up a spur track ending just below the summit of Pu‘u Manukani. As I walk through the damp Kikuyu grass to the top of the pu‘u, the vast lowlands of Kahikinui spread out before me. I gaze down on the Luala‘ilua Hills to the southwest (see fig. 14). When I turn toward the east, St. Ynez Church is a mere speck in the far distance. The view takes my breath away. Yet I am only one-third of the way up the slope of Haleakalā. Looking mauka, I can make out the remnants of the upper dry forest on the higher slopes, dominated by koa trees catching the midday fog drip. The forest line gives way at about 1,800 meters to subalpine scrub dominated by gnarly pūkiawe (Styphelia tameiameiae). Perched at 2,199 meters is the cinder cone of Kahua. Above that lies the rim of the great Haleakalā crater itself, where the famed silver swords, or ‘āhinahina (Argyroxiphium sandwicense), grow in an alpine desert.

The Luala‘ilua Hills as seen from the summit of Manukani; the tip of Kaho‘olawe Island is visible in the distance.

Although they lived their lives mostly in the zone below Manukani, where the conditions were suitable for sweet potato and dryland taro gardens, the Hawaiians of ancient Kahikinui and East Maui were not entirely unfamiliar with these highest mountain regions. Within the vast crater of Haleakalā are stone platforms and terraces, some containing burials, first documented by

Kenneth Emory of the Bishop Museum in 1920. On one of the highest peaks above Kahikinui there stands to this day a heiau platform. Who built it, and when, remains a mystery. Yet it persists as a symbol of how nā kua‘āina claimed the land of Kahikinui, Great Tahiti, from the shoreline to the very peak of its great mountain.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 2 |

| March 2024 | 2 |